Despite higher prices, debt levels continue to rise in many energy exporters. Now is no time for complacency.

Summary

Although many energy-exporting countries have taken unprecedented steps to reduce their reliance on the oil and gas sector, dependence remains high. However reform urgency is easing as price outlooks improve.

Despite the strong policy trends toward decarbonisation of the energy mix, rapidly growing populations and economies, especially in Asia, are expected to put upward pressure on oil and gas prices to 2025. Risks to the price outlook lean to the downside as the energy transition could occur faster than expected.

Higher prices would certainly provide some breathing space to these vulnerable countries. Using a scenario analysis, we project twin deficits in all vulnerable countries to reduce between 2018 and 2025. But public debt levels are likely to continue rising in many countries. Bahrain is the most vulnerable with high and rising public debt, and low buffers to mitigate short-term volatility.

We conclude that now is no time for complacency: despite higher prices, deficits will soon become more expensive to finance and public debt levels remain high, and even rising in some countries.

Little progress in reducing vulnerabilities

Despite more than three years of low commodity prices, the reliance on oil- and gas-related revenues for most top fuel-exporting countries has not significantly declined. The small declines that do exist are likely attributable to price effects than to reforms. Economic diversification thus is progressing very slowly. In this note, we zoom in on the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a group of energy-dependent countries in the Persian Gulf.

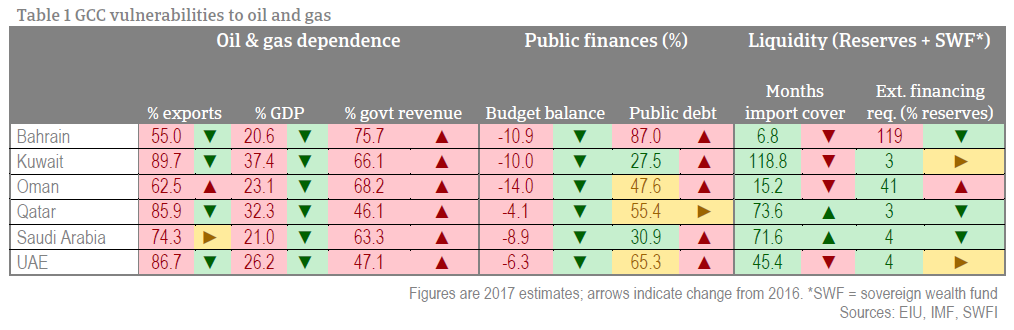

An overview of GCC countries’ vulnerability to oil and gas prices is presented in Table 1. This group stands out in respect to overall dependence across each key economic aspect. 76% of GCC exports are oil- and gas-related and 61% of government revenues come from these activities. Oil and gas account for an average 27% of GDP too. Across all three indicators, all six GCC members are in the red, indicating high vulnerability.

Looking to public finances, most of these energy exporters still have wide annual budget deficits and rising public debt levels – Qatar is the only exception whose public debt stabilised in 2017. Many governments have cut energy subsidies and curtailed capital spending in order to reduce dependence on energy revenues, which has contributed to narrowing budget deficits. These efforts are not reflected though in share of total government revenue, as these have increased in each country.

Overall, compared to many other vulnerable energy exporters, like Ecuador and Congo, the GCC countries associated with short-term volatility in energy prices. However, the past episode of low oil prices has eroded some of these buffers as these countries have resorted to tapping their sovereign wealth funds in order to finance deficits. Reserves have been used to defend currency pegs in the GCC countries and also by Qatar to counter capital flight after the regional boycott.

The GCC countries have initiated national development plans to diversify their economies away from hydrocarbons, but this is a very gradual process. In the short-term, dependence on commodities will persist and the latest rebound in prices from their lowest point has reduced the sense of urgency to undertake reforms. Social discontent with fiscal austerity and low economic growth are already causing some authorities to refocus their policy back to boosting short-term growth.

The current environment of cheap and easy funding offers ample access to money on international capital markets to finance deficits which further reduces the urgency for fiscal austerity. But as interest rates continue to rise, debt-service costs will increase, pushing up financing risk over the forecast period. This is especially alarming for those countries that have also seen significant erosions in their financial buffers.

Oil & gas outlook – global energy mix in flux

While little progress has been made in addressing energy dependence in the GCC and at the global level, the more positive outlook for energy prices offers some optimism. This should provide some relief, but looking forward to 2025, oil and gas prices will remain significantly below the levels seen in the early 2010s. This is in large part due to major changes underway in the energy mix.

Low-carbon energy sources – like renewables, natural gas and, to a lesser extent, nuclear – are rapidly gaining ground. Heavy investment is improving the technology and bringing down costs. China’s energy revolution to address air pollution and invest heavily in renewables is supporting this and is offsetting some demand growth for conventional energy sources. On the supply side, the US energy sector has demonstrated remarkable resilience and its shale revolution continues to surprise to the upside.

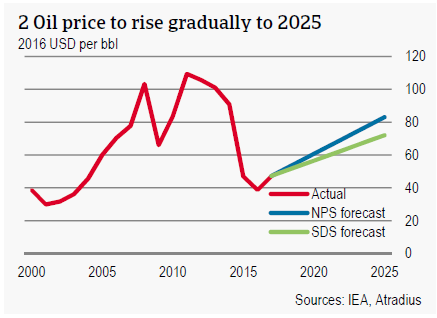

All these trends point to downward pressure on oil prices as more efficient energy and government policy reduces demand for fossil fuels and oversupply persists. However, prices are expected to rise from 2018 to 2025, due to rising energy demand growth. Energy demand has surprised to the upside over the past year and should stay strong this year as the global economy enjoys robust growth. High GDP and population growth, particularly in Asia, should continue to feed the growing demand for energy into 2025. While this will be partly offset by the aforementioned changes in the energy mix, it will be sufficient to push prices higher.

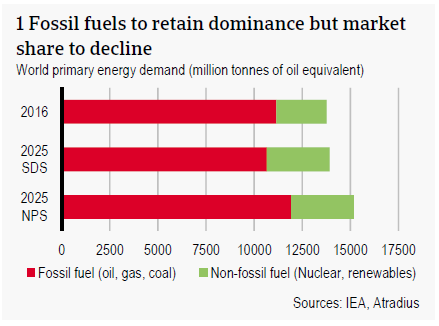

It is in this context that we base our outlook on the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) New Policies Scenario (NPS), as presented in its World Energy Outlook 2017. This scenario is characterised by global adherence to existing environmental legislation and announced policy intentions. The forecast 25% growth in renewables and nuclear energy however will be insufficient to meet higher demand from emerging markets, offering better prospects for the oil and gas industries which would need to expand production 7%. In order to meet this demand, prices of oil and gas are thus set to rise to USD 83 per barrel (in real 2016 USD).

An alternative scenario, put forth by the IEA, is the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS). The SDS is far more ambitious in achieving environmental goals and universal access to electricity as spelled out in the UN Sustainable Development Goals and effectively points to stagnating energy demand. This world requires a major policy push from governments and more than 15% higher investments than in the NPS. We think this is unrealistically optimistic at this moment but opt for the SDS as an alternative scenario since lower-than-expected energy prices would weigh further on public finances on energy exporters without effective diversification.

Non-fossil fuels would also grow 25% from 2016 to 2025 in the SDS, but overall demand would only grow 1%. Demand for oil and gas would decline about 4% and the price of a barrel of Brent would only reach USD 72 by 2025. In both scenarios, oil and gas prices are set to stay well above levels seen from 2014 to 2017.

Brighter outlook but debt levels still rising

Rising prices will provide some breathing room for oil- and gas-exporting countries. This should bode well for their finances and economies. Here we run a scenario analysis, looking specifically at the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, to assess the impact. Using the Oxford Economics global economic model, we insert the price paths of oil (Brent) and gas (Henry Hub, Japanese LNG, and North Sea) without making any further assumptions. The focus is on first-round effects, so feedback loops of the imposed oil and gas prices are not allowed to feed back again into prices.

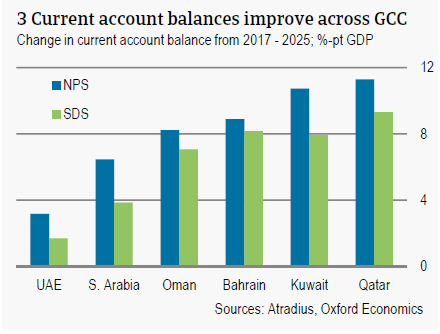

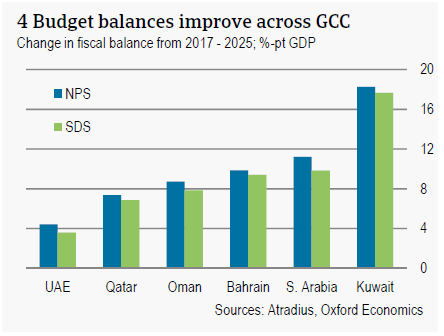

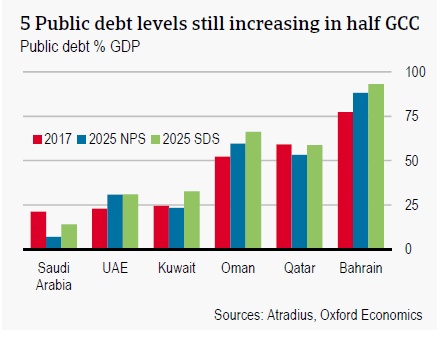

As both scenarios envisage substantially higher oil and gas prices than in the past few years, budget and current account balances generally show improvements (see figures 3 and 4). These improvements are most notable for countries in the Middle East and are strongest in the higher-price NPS.

For the change in public debt ratios however, the results are mixed. Half of the countries show an increase in debt levels, even in the NPS. This is an indication that additional measures need to be taken to shore up their finances despite the more favourable price outlook. This especially holds for Bahrain, for which the public debt level will be the highest – around 90% of GDP in 2025. Bahrain’s liquidity position is also weak, making it difficult for the country to cope with price fluctuations in the short- to medium-term.

Some breathing room but no time for complacency

Despite the transformation of the energy mix toward renewables and greater energy efficiency, robust demand growth from emerging economies will force the price of oil and gas upwards to 2025. Although this is expected to provide some relief for many countries, failure to diversify away from hydrocarbons will leave these countries susceptible to price developments.

Thus far, GCC countries have undertaken painful reforms to reduce reliance on this sector, but this is a slow process and reform fatigue is increasing. Despite improvements in budget and current account deficits and their positive outlooks, financing of them is expected to get more difficult. Reserves generally remain sufficient at this point to meet financing requirements and global financial conditions are extremely loose. However, decreasing reserves and more expensive credit could increase financing risks over the forecast period, especially as public debt levels continue to increase. It is clear that simply a higher price outlook should not support complacency in energy exporters.

Finally, the transformation of the energy mix suggests strong growth opportunities in renewables whereas fossil fuel demand eases. This transition could come along much more quickly than expected, as technological breakthroughs are impossible to predict. Energy exporters must continue preparing themselves for this energy mix transformation.

An alternative scenario, put forth by the IEA, is the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS). The SDS is far more ambitious in achieving environmental goals and universal access to electricity as spelled out in the UN Sustainable Development Goals and effectively points to stagnating energy demand. This world requires a major policy push from governments and more than 15% higher investments than in the NPS. We think this is unrealistically optimistic at this moment but opt for the SDS as an alternative scenario since lower-than-expected energy prices would weigh further on public finances on energy exporters without effective diversification.

Non-fossil fuels would also grow 25% from 2016 to 2025 in the SDS, but overall demand would only grow 1%. Demand for oil and gas would decline about 4% and the price of a barrel of Brent would only reach USD 72 by 2025. In both scenarios, oil and gas prices are set to stay well above levels seen from 2014 to 2017.